We shouldn’t call 2021’s exams ‘GCSEs’ and ‘A levels’

Strange days indeed. And so the nightmare of 2020 continues, a little like Donald Trump (perhaps less orange but still ignoring the conventions of the calendar) - causing havoc and generally outstaying any welcome on a truly epic scale.

Meanwhile, 2021 (or 2020. 2.0, as it is currently known in its frankly disappointing beta phase) looks like a bad upgrade on the preceding year, a sequel bereft of the surprise factor.

We seem to be living in a series of thought experiments, each day a Crystal Maze of mind-bending unpredictability. Or we’re in a Sartre play, desperate to leave our locked-down bubbles but stuck in the same place, a no-escape room, knowing that even if we were to go elsewhere, it would look exactly the same as here: grey, empty, half-masked but with the tiers still visible.

Things change but stay the same. And not for the first time, schools seem to be one of the flickering shapes on the near horizon for all those who have some vested interest in them. Open, closed, a little bit open to some, closed to most...offering or not offering lateral flow tests and, possibly, qualifications of some sort.

Coronavirus: When are GCSEs and A levels not GCSEs and A levels?

The latest act from the Department for Education (the only West End farce that is still being performed, albeit to empty houses and despite terrible reviews) reads like a question from an A-level examination (remember them?). It recalls Hobbes’ Ship of Theseus paradox: when does a ship become a different ship? Or, to bring it into a modern context: when do GCSEs and A levels become different qualifications altogether?

In Hobbes’ brainteaser, we are asked to consider the nature of identity, and whether it is retained through sustained change. If Theseus replaces each part of his ship - plank by plank, sail by sail - at what point does he have an entirely new ship? Or is it still his old ship? Or does he have two ships (one physical, one historical)?

This problem of vagueness is that it’s difficult to find definite answers to (although, to be fair, the secretary of state seems to have adopted this position as his entire raison d’être), but it raises a serious question about the current and future perception of our national school qualifications.

To what extent are the qualifications that our current Year 12s and first-year undergraduates hold GCSEs and A levels? The same question applies to the qualifications that are going to be awarded in the summer through teacher assessment.

Take away a question in English language paper 1, or even a whole module, and most people would say that it still looks like the same GCSE. But take away the whole paper?

The secretary of state just did a Theseus with every key stage 4 and 5 qualification. Time, which glues changes together so that we accept them as evolution, sped up. Change happened on a monumental scale. The names are retained as carapaces - veneers of normality.

Getting rid of all examinations

If you get rid of all the examinations, and every part of the assessment, what do you have? What if much of the content goes, as well as a significant part of the teaching? What’s left? What part of the qualification is still core A level or GCSE?

If we insist that they should carry the same names, then what were the qualifications that were awarded before the pandemic? Were they different? Yes, they were. Were they superior? Well, yes, because nobody would say we’ve replaced what we had with something superior in any way. Nobody wants to stick with this. Are the grades the same? Clearly not.

Are we only retaining the labels “GCSE” and “A level” because, collectively, we either lack the imagination to provide alternative names, or we can’t be bothered to think about what these qualifications actually are, or what they are intended for?

But names matter: they signify accuracy, consistency. The reality is that, by distinguishing these two unusual years, we will establish greater clarity, both to the qualifications being calculated at this time, as well as to those that have preceded them (and, hopefully, those that will follow).

Clearly a grade achieved under timed conditions, across several papers, and marked externally is different in kind (I am not saying one is better than the other) than a grade arrived at by a teacher attempting not only to accurately reflect progress over two uneven years but also to predict future attainment.

We should rename these qualifications so that they accurately describe what they are: key stage 4 and key stage 5 school-assessed qualifications. The grade set, too, should not seek to imitate GCSE and A level but should be wider - pass, merit, distinction - so that it can capture the vastly different experiences that our students have grappled with, as well as their effort and achievement. This would also allow teachers, universities and employers to measure suitability for the next stage of a student’s education.

Of course, given the track record of our current secretary of state, nothing sensible will happen until it is so late that it almost ceases to be advisable.

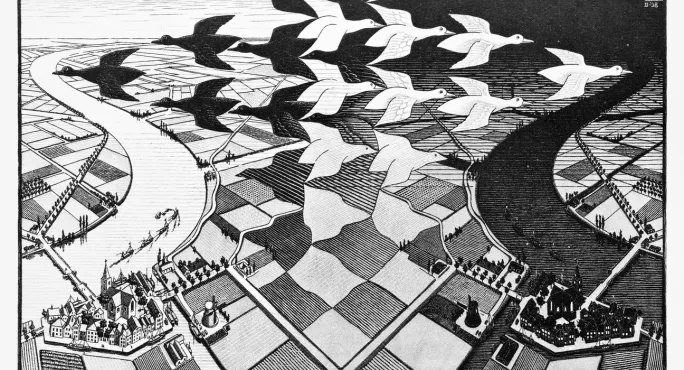

Perhaps we will be forever left with another philosophical paradox: the duck-rabbit, in which an image simultaneously depicts both a duck and a rabbit. Just as the person who is looking at the image sees both the duck and the rabbit, so we will always have to try to see these Covid-qualifications as at once GCSEs/A levels but also not GCSE/A levels.

But no matter how hard we try - as with the duck-rabbit - the one will never really be the other.

David James is deputy head of an independent school in London. He tweets as @drdavidajames

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters